09/01/2024

Haemochromatosis is the UK and Irelands most common inherited condition and is thought to be severely underdiagnosed. The prevalence of haemochromatosis among individuals of white ancestry is estimated to be approximately 1 in 300, notably observed across Europe, Australia, and other nations with significant populations of Celtic descent1, hence the colloquial name – The Celtic Curse. However, while haemochromatosis is more common in these populations, it can affect people of any ethnicity or background. It’s also quite a bit of a tongue twister…

Symptoms of Haemochromatosis

- Fatigue

- Weight loss

- Weakness

- Joint pain

- Erectile dysfunction

- Irregular, stopped or missed periods

- Brain fog

- Mood swings

- Anxiety

- Depression2

Haemochromatosis is a genetic disorder that over time causes an iron overload within the body that can lead to conditions such as cirrhosis, liver cancer, diabetes, arthritis, and heart failure2. With an NHS expenditure of around £487 million annually3, this condition carries a significant burden on healthcare services.

While the name is complicated, our message is simple: Early identification saves lives!

Key Facts.

- Approximately 9 million people in the UK are estimated to have 1 of the 5 genetic mutations associated with Genetic Haemochromatosis (GH)3.

- £ 487 million annual NHS expenditure – Over 55% of which is used in treatments for GH-induced liver disease, liver cancer, diabetes, arthritis and more3.

- In Northern Ireland, as many as 1 in 10 people are directly affected by haemochromatosis4.

- In the UK, estimates claim that 380,000 people are directly affected by haemochromatosis, however only 14,000 people have been identified by the NHS5.

Iron Overload

Iron is an essential mineral required for various processes including DNA synthesis and oxygen transport7.

In contrast to other minerals in the body, iron excretion is an unregulated process, meaning the control of iron levels is exclusively the responsibility of absorption7. Some believe this is due to the historical lack of iron in the human diet resulting in an evolutionary propensity for iron accumulation.

When iron is excreted, it’s in unregulated amounts in the form of sweat, during menstruation, through the shedding of skin and hair cells or through the turnover of enterocytes (cells of the small intestine crucial in nutrient absorption)7.

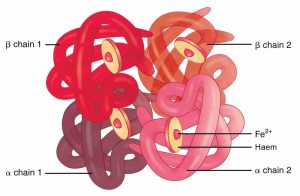

Most of our iron is found in haemoglobin, the protein in red blood cells responsible for transporting oxygen around the body7 – oxygen binds to the iron, or the haem groups, of haemoglobin.

Within one haemoglobin protein are four haem groups each containing an iron molecule, enabling the reversible binding of four oxygen molecules. This provides an efficient means of transporting oxygen throughout the body.

Iron is exceptionally well-suited for its crucial role in various biological processes due to a combination of unique factors. Its distinctive chemistry allows it to undergo oxidation-reduction reactions, which are pivotal for functions such as oxygen transport, energy production, and DNA synthesis.

The Genetics

Haemochromatosis is an autosomal recessive disorder meaning for a person to suffer with this condition, they need to have 2 faulty copies of the gene. If an individual only has 1 faulty copy and 1 working copy they are considered a carrier – there is a 50% chance they’ll pass this gene on to their offspring. For a more detailed explanation, check out our blog, Genetic Inheritance and Conditions.

With the Celtic Curse, these variants, or mutations, occur in the gene responsible for the HFE protein. This mutant HFE protein causes an increase in iron absorption and the subsequent deposition of iron into various organs2.

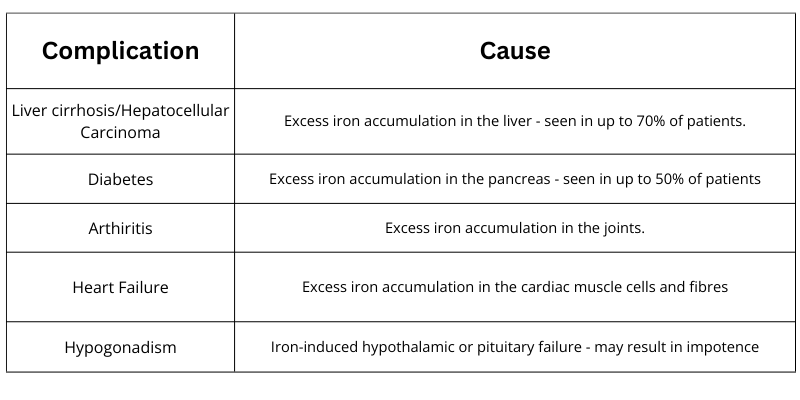

The most common genetic mutation responsible for haemochromatosis is the C282Y variant. This variant also causes more severe symptoms than the next most common variant, H63D1. Those who carry two copies of the C282Y variant are at a much higher risk of iron overload and the associated complications, shown in the table below1. Its also important to note that these complications, particularly those related to the liver and pancreas, can be exacerbated by high alcohol intake and viral hepatitis1.

Individuals with H63D variants are generally asymptomatic, however, if iron levels increase above normal, investigation is required as there may be another reason for this rise8.

Some people harbour a copy of each of these variants (C282Y and H63D), referred to as compound heterozygous. 95% of people with this genotype are asymptomatic, however, the remaining 5% of patients should seek to monitor their iron levels every few years to avoid any severe complications8.

If identified before organ damage has occurred, treatment of haemochromatosis is straightforward and successful. Generally, restricted diets are not recommended. However, in some cases, patients will be encouraged to reduce their intake of iron through things like red meat, poultry, and pork, which contain high levels of iron and are easily absorbed.

Some foods like leafy greens and dairy products or tea and coffee can help slow down the absorption of iron and may be considered along with foods high in iron8.

Testing at Randox Health

At Randox Health, we offer genetic testing to determine if you’re at high risk of haemochromatosis.

Early identification allows the treatment and the prevention of a variety of forms of ill health that can result from iron overload. Once your results are available, you’ll get a genetic risk report which will show a breakdown of your results and explain exactly what they mean. For more information, visit our website at https://randoxhealth.com/en-GB/in-clinic/haemochromatosis

- Porter JL, Rawla P. Hemochromatosis. Stat Pearls Publishing LLC; 2023.

- NHS. Haemochromatosis . Health A to Z. Published March 29, 2023. Accessed December 11, 2023. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/haemochromatosis/

- Haemochromatosis UK. Evaluating the Cost of Illness of Genetic Haemochromatosis in the UK. haemochromatosis.org.uk. Published 2023. Accessed December 11, 2023. https://www.haemochromatosis.org.uk/cost-of-illness

- Haemochromatosis UK. Diagnosis & care. haemochromatosis.org.uk. Published 2023. Accessed December 11, 2023. Haemochromatosis

- Neil McClements. It’s Time For Change – towards Genetic Screening in Adults across the UK.; 2021.

- Sheftel AD, Mason AB, Ponka P. The long history of iron in the Universe and in health and disease. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) – General Subjects. 2012;1820(3):161-187. doi:10.1016/j.bbagen.2011.08.002

- Ems T, St Lucia K, Huecker MR. Biochemistry, Iron Absorption. Stat Pearls Publishing LLC; 2023.

- Haemochromatosis UK. Genetics of Haemochromatosis. haemochromatosis.org.uk. Published 2023. Accessed December 11, 2023. https://www.haemochromatosis.org.uk/genetics-of-haemochromatosis

- British Liver Trust. Hereditary Haemochromatosis, a common gene disorder causes serious “stealth” disease, but could be easily treated. britishlivertrust.org.uk. Published 2019. Accessed December 11, 2023.