03/07/2024

Earlier this year, a study published in the Lancet reported that over 1 billion people globally are clinically obese1. Obesity has been a known public health threat for over 20 years, yet the numbers continue to rise. It’s caused when extra calories, especially those from food high in sugar and fat are stored in the body.

There are many factors influencing a person’s weight. Hypothyroidism can cause excess weight gain. As can some medications for high blood pressure, diabetes, or mental health conditions. Perhaps less intuitively, genetics can play a role in a person’s risk, and the development of obesity2.

Our Nutrition and Lifestyle DNA test analyses your genes to determine how your body responds to the foods you eat and how your genes can affect your weight, physical activity, injury risk, mental health, and sleep, as well as a range of nutritional diseases, to empower you with the information you need to personalise your nutrition and training plan. In this blog, we’re going to look at obesity, the genes involved, and how information on your genetic variants can help you improve your wellbeing.

Obesity.

This chronic and complex disease is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as excessive fat deposits that can impair health3 through changes in the body’s physiological and hormonal environments. Obesity results from an imbalance of energy intake, from the food you eat, and energy expenditure, the physical activity or exercise you do. However, maintaining this balance isn’t always easy. Sometimes that slice of cake looks too good or it’s a little too cold to go for a run.

In most cases though, obesity is multifactorial. Yes, if you regularly overeat, there’s a good chance you’ll become overweight or obese. However, there are other contributing factors. Genetics, medications, and medical conditions, as well as environmental factors like lack of access to healthy, affordable food, are among the causes which can affect a person’s risk of obesity2.

Obesity isn’t just about aesthetics either. It can have some rather serious effects on your short- and long-term health. Obesity can cause breathlessness, fatigue, increased perspiration, reduce a person’s self-esteem and contribute to depression2. In the longer term, obesity can contribute to the development of life-altering conditions such as type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease (CVD), metabolic syndrome, asthma, gallstones, liver disease, kidney disease, and several forms of cancer2. Obesity can also reduce fertility and increase the risk of pregnancy complications like pre-eclampsia or gestational diabetes2. Finally, sleep and weight are closely linked. Obesity can increase the risk of developing sleep apnoea which can affect your day-to-day energy levels, and further increase your risk of CVD and diabetes. The NHS state that, depending on its severity, obesity can reduce life expectancy by 3-10 years2.

The most straightforward way of finding out if you are obese is by calculating your BMI. If you’re interested, you can use the NHS BMI healthy weight calculator. It’s important to note that BMI score has some limitations as it measures the weight people carry. For example, those who are very muscular have a high BMI with a low body fat percentage. You can see the ranges in the table below:

| BMI | Category |

|---|---|

| For most adults: | |

| Under 18.5 | Underweight |

| 18.5 – 24.9 | Healthy weight |

| 25 – 29.9 | Overweight |

| 30 – 39.9 | Obese |

| 40 and above | Severely obese |

| For adults of Asian, Chinese, Middle Eastern, Black African, or African-Caribbean family background: | |

| 23 – 27.4 | Overweight |

| 27.5 and above | Obese |

The Genes.

The fat mass and obesity associated (FTO) gene was the first to be undisputably associated with fat accumulation, or adiposity, and inspired much research into the association of genetics and obesity4. FTO is expressed in adipose (fat) and skeletal muscle tissue. However, its highest expression is in the hypothalamus, the brains hormonal command centre. Here, FTO is thought to be involved in appetite regulation and energy metabolism by affecting hormones related to these processes4. Several single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), single-letter genetic variations occurring commonly within a population, have been strongly associated with body fat rate, waist circumference and energy intake4.

Mutations in the melanocortin 4 receptor (MC4R) gene are the most common monogenic (traits or disorders caused by mutations in a single gene) cause of severe early-onset obesity – around 5% of those with severe childhood obesity harbour a pathogenic MC4R variant5. Like FTO, MC4R is highly expressed in the hypothalamus and is an important regulator of appetite and body weight6. Loss of function of this gene can disrupt the normal signalling processes involved in the regulation of food intake and energy homeostasis, resulting in increased body weight and obesity7. Its not all bad news with MC4R, however. Gain of function mutations have also been identified which infer a level of protection against obesity8.

As with all genetic analysis of this type, its important to remember that having a pathogenic variant doesn’t mean you will develop obesity, and having a protective variant doesn’t mean you won’t. It simply means that you harbour a genetic predisposition – other physiological and environmental factors play a role too.

If the genes fit…

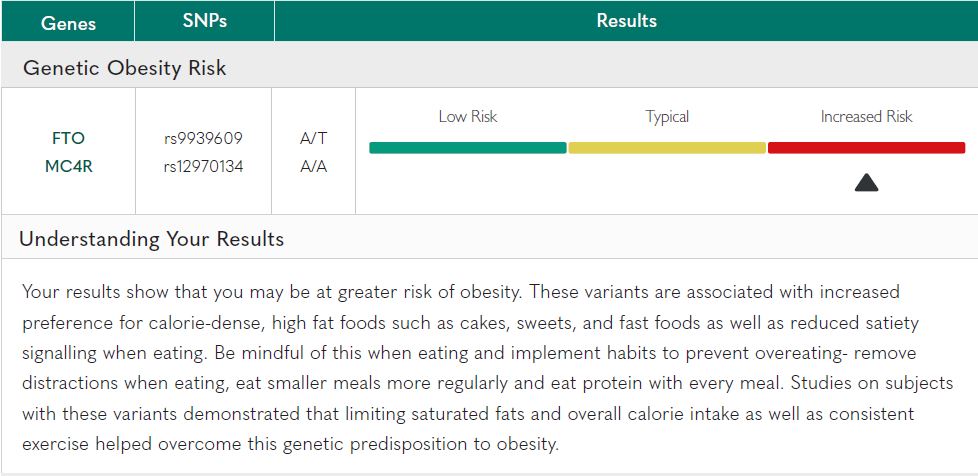

Difficulty losing weight, low energy levels, food intolerances and other health problems could be addressed by understanding your genetic makeup and the impact of your diet and lifestyle. Our Nutrition and Lifestyle DNA test is designed to explore the relationship between nutrients, diet, lifestyle factors, and gene expression. As part of this genetic analysis, we look at your variants of FTO and MC4R to determine your genetic predisposition to obesity.

The results of your genetic obesity risk will be in your report, along with the other 38 genes we investigate. We’ve thought long and hard about these reports. We want the information to be as simple and accessible as possible.

In your report, the names of analysed genes are given along with an ‘rs’ number for each variant analysed in that gene. The ‘rs’ number is simply a unique ID number given to a genetic variant. Variants are represented by 2 letters (e.g. A/A) which represent the base pair present at the analysed location of the gene. A visual scale is included to help you gauge your results and we provide a detailed description of your results and their potential implications. Finally, we provide a glossary of all the terms you may come across in the report to make sure you fully understand the information your provided with. You can see an example below.

To book your Nutrition and Lifestyle DNA test, visit our website. All you need to do is book an appointment at a time and date that works for you. During your appointment we’ll just take a simple blood sample, and you can get back to your busy schedule. All that’s left to do is wait! You’ll get your report within 4-6 weeks.

References

- Phelps NH, Singleton RK, Zhou B, et al. Worldwide trends in underweight and obesity from 1990 to 2022: a pooled analysis of 3663 population-representative studies with 222 million children, adolescents, and adults. The Lancet. Published online February 2024. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(23)02750-2

- NHS. Obesity. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/obesity/.

- World Health Organisation. Obesity and overweight.

- Lan N, Lu Y, Zhang Y, et al. FTO – A Common Genetic Basis for Obesity and Cancer. Front Genet. 2020;11. doi:10.3389/fgene.2020.559138

- Chami N, Preuss M, Walker RW, Moscati A, Loos RJF. The role of polygenic susceptibility to obesity among carriers of pathogenic mutations in MC4R in the UK Biobank population. PLoS Med. 2020;17(7):e1003196. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1003196

- Wang X, Cui X, Li Y, et al. MC4R Deficiency Causes Dysregulation of Postsynaptic Excitatory Synaptic Transmission as a Crucial Culprit for Obesity. Diabetes. 2022;71(11):2331-2343. doi:10.2337/db22-0162

- Yeo GSH. Mutations in the human melanocortin-4 receptor gene associated with severe familial obesity disrupts receptor function through multiple molecular mechanisms. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12(5):561-574. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddg057

- Lotta LA, Mokrosiński J, Mendes de Oliveira E, et al. Human Gain-of-Function MC4R Variants Show Signaling Bias and Protect against Obesity. Cell. 2019;177(3):597-607.e9. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2019.03.044